NOTE: This is an adaptation of the readme for a repo you can find here

Relational Databases remain to be an industry standard. These store knowledge in rigidly defined schemas, which makes them easy to understand, troubleshoot, implement and interact with. Graph Databases present an alternative to Relational DBs - storing data in an intuitive format with more flexible schemas. These work well for representations of networks - electrical networks, communications, logistics, etc.

A common problem in software development is poor data quality. In my experience, a common feature of issues relating to data quality is that the requirements of the system in question have changed since its design. For example, a job scheduling register initially designed for humans to interact with suddenly requires machine interaction, and existing free-text fields in the register are unsuitable for that. Or, a rust-prevention programme of work requires data estimating rainfall at each asset, and the schema doesn’t have such a field. The rigidity of the relational database schema becomes a restriction rather than a benefit here. To estimate rainfall and understand the free-text fields, we’ll likely have to move out of the database and into ad-hoc local data manipulation.

Data quality issues seem unrelated to the type of database - relational, graph, whatever - we select. These methods have difficulties in that editing their schema to support new concepts and populating the new schema with accurate information is a costly exercise.

I have a theory that semantic spaces (read: embeddings models) could be a method of storing knowledge that would have a much easier time adapting to changing requirements, and therefore be more resilient to data quality issues.

Further, fine-tuning foundational embeddings models (which capture general knowledge of the world) to organisational data (which capture organisational knowledge) could enable a potent general analysis capability. Organisations would be able to rapidly connect internal concepts to world concepts, circumventing the need for expensive data collection tasks.

For example, say at a Transmission Utility, we had a record in a database representing a tower “TWR-89047882”. We can picture what that number represents because we have world knowledge of what a transmission tower looks like, what purpose it serves, et cetera. If we saw a Location of “London” against that tower in the database, we would actually understand quite a lot about what that tower’s existence might look like - only having seen a few bytes of data. If we were to fill out a column “Weather” against each tower, we wouldn’t have to think hard before we wrote “Rainy” in that row.

Let’s say we have a predictive maintenance software that automatically generates maintenance work orders. For its rust-prevention maintenance module, it requires data on the weather conditions at each asset. Systems such as this maintenance software do not have the benefit of this world knowledge. We have to hire a data analyst or data scientist to join some weather data to each Tower such that the rust-prevention module will issue the correct work orders.

Now suppose we have the proposed embeddings model from earlier - a foundational embeddings model fine-tuned such that the organisations’ relational data could be extracted. It’ll place the string “TWR-89047882” at some location in semantic space. We should be able to navigate to its Location - London - nearby. The model will already have London quite well understood, so we should be able to make an additional hop to “Rainy”. Our predictive maintenance software is now happy, and we didn’t even touch a jupyter notebook.

It’d be like having human knowledge available to fill out any column against your relational data - feeding many studies, programmes of work and analyses that would otherwise require significant effort.

In this way, semantic knowledge stores could present a transformative database technology. However, the practicality of such a database, reliability, implementation details, strengths, weaknesses and interaction modes are unclear.

How are facts represented in Semantic Space?

There are no explicit facts in this space as in a Relational DB, Graph or Triplestore - just associations of varying strength. However, we can learn to explore the space to extract information similar to a traditional DB.

If meanings of symbols (words) are represented by position in semantic space, then relationships between symbols are represented by displacement.

This is actually exemplified in the popular “king and queen” example. With a trained embeddings model, we can take the vector produced from the word queen, subtract the vector for the word woman and add the vector for man and arrive at/near king. We took a known relationship and applied it to a symbol in the same category - effectively learning how to explore the semantic space for gender-counterpart relationships. Experiment 1 pushes this idea slightly further.

Experiment 1: Learning to Explore Semantic Space

The king and queen example suggests we can find facts - like querying a database - by exploring semantic space. Let’s have a go at doing this.

I’m going to start with the simplest example. I went with a pretrained word2vec embedding model, 'word2vec-google-news-300'.

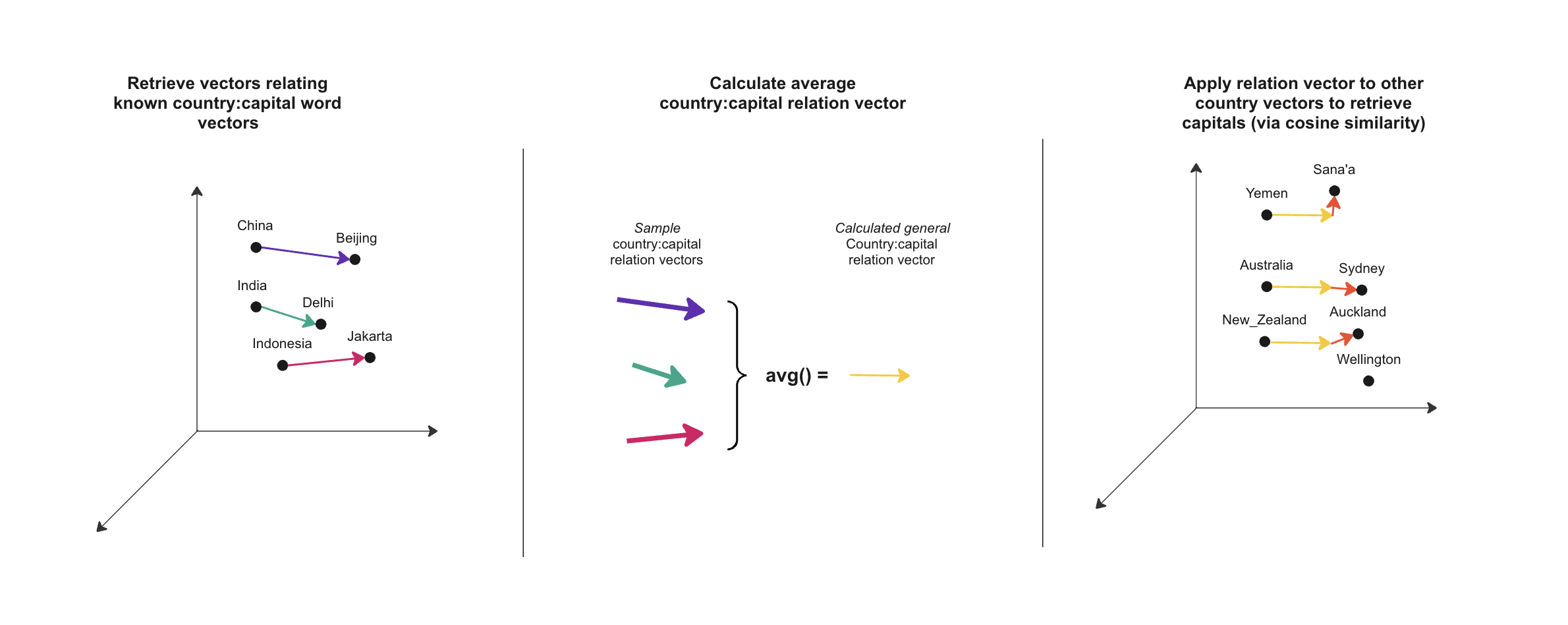

In countries_to_capitals.py, I’ve built a script which takes twenty country-to-capital pairs and averages the vectors relating each, attempting to yield a vector which could be used to retrieve the Capital city of a wider sample of countries.

Results

| Country | Capital | guess_capital |

|---|---|---|

| China | Beijing | Beijing |

| India | New_Delhi | Delhi |

| United_States | WashingtonDC | Washington_DC |

| Indonesia | Jakarta | Jakarta |

| Pakistan | Islamabad | Islamabad |

| … (40 records omitted) … | ||

| Yemen | Sana’a | Sana’a |

| Madagascar | Antananarivo | Antananarivo |

| North_Korea | Pyongyang | Pyongyang |

| Australia | Canberra | Sydney |

| Ivory_Coast | Yamoussoukro | Abidjan |

Number of correct guesses: 39 out of 51 records.

Thoughts

This is a scaled-up version of the king and queen example we looked at above. It appears to work decently. However, we took a shortcut in that we had a list of countries to begin with. Plus, we needed to calculate a relationship vector from a considerable sample of known values.

Experiment 2: Retrieving Similar Relationships from Semantic Space

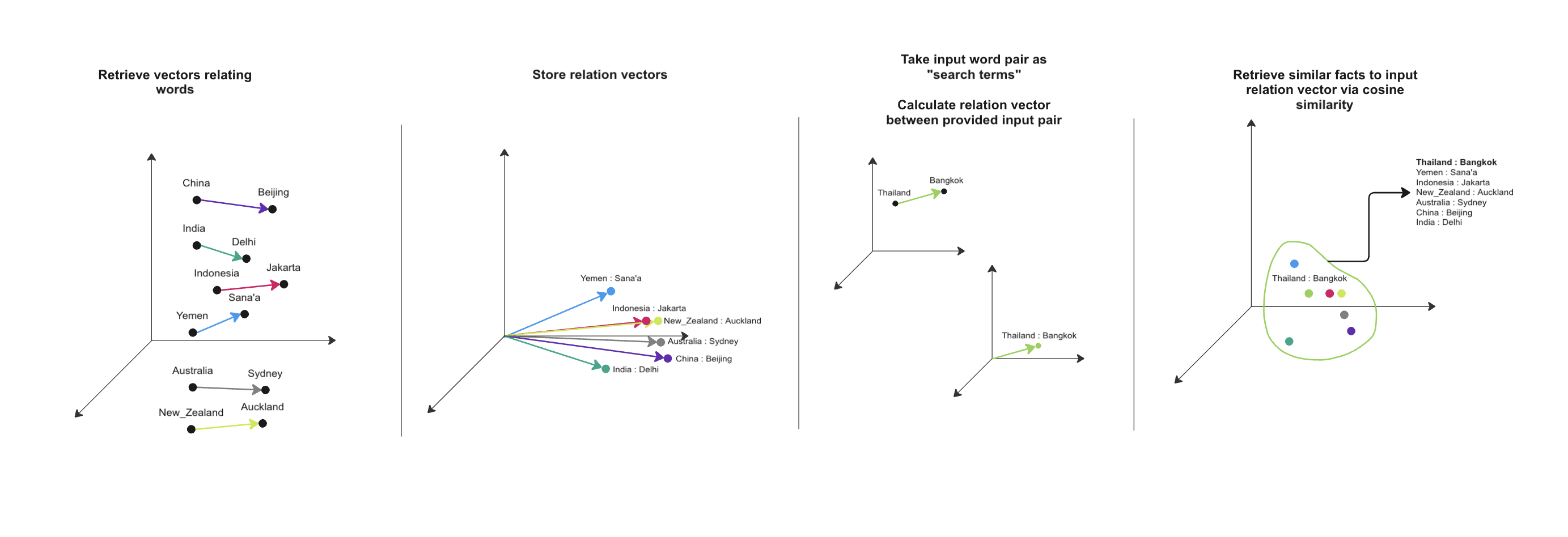

I had an idea that we could store a relation vector in the same way we store a word vector. From there, we could use traditional clustering and similarity measures to retrieve pairs of symbols with similar relationships. This experiment somewhat generalises the approach used in Experiment 1.

In save_relations.py, I’ve built a script which takes the most popular terms in the model’s vocabulary and saves the relation vectors between each, as above. This is a memory-heavy process, so I’ve used .h5 binaries for storage. You can then provide a pair of words that you know are related, and the script will find the most similar relation vectors. I had to filter these so that duplicate values are removed, so it only really supports one-to-one relationships.

Results

python save_relations.py 20000

python explore_relations.py China Beijing

| left | right |

|---|---|

| Russia | Moscow |

| Korea | Seoul |

| Malaysia | Kuala_Lumpur |

| Japan | Tokyo |

| Turkey | Ankara |

| … (14 records omitted) … | |

| India | Delhi |

| Thailand | Bangkok |

| Egypt | Cairo |

| Pakistan | Islamabad |

| Indonesia | Jakarta |

python explore_relations.py federer switzerland

| left | right |

|---|---|

| Switzerland | Roddick |

| Germany | Agassi |

| Italy | Safina |

python explore_relations.py mouse murine

| left | right |

|---|---|

| RA | keyboard |

| IL | button |

| ii | wizard |

| RNA | app |

| NA | locate |

Thoughts

For the Country-to-Capital example, of 100 similar examples, we get 24 that are valid pairs (i.e. not duplicates). Most of these seem correct.

Unfortunately, the quality of results degrades rapidly as we try less prominent words. I’m guessing there is less information on Animal-to-Class relationships than Country-to-Capital relationships in the training data for 'word2vec-google-news-300'. The idea of a signal-to-noise ratio comes to mind here.

This Word2Vec model is quite lightweight - a couple of gigabytes and 300 dimensions. It may be that a larger, say, Sentence Transformer type model would capture relationships in more niche topics with more detail.

Future Work

-

Investigating Training on Organisational Data

We glossed over that we could have foundation models fine-tuned on organisational data - that’s definitely possible, but to serve as a general-purpose database the schema of the existing databases would need to be preserved.

We’d need to devise a method of fine-tuning that would allow the hard relationships stored in a relational database to be converted into associations in semantic space, in such a way that we can reliably query the (ex-)relational data, but also connect that data to world concepts.

-

Toy Example

At the moment the “Semantic Database” has been proposed alongside some short python scripts and conjecture. It would be useful to provide some more concrete evidence of the idea’s validity.

Firstly, we could set up a low-dimensional space with arbitrary symbols to demonstrate the capability of relating organisational data from a rigid schema to broader concepts. We know this is possible though.

To fully demonstrate plausibility, you could go as far as generating simple data (say, a fictional table of Asset data) and finding a way to fine tune an existing model such that these Assets land in a sensible location in semantic space.

One method I can think to achieve this would be - as ridiculous as it sounds - to use an LLM to generate screeds of articles about organisational symbols based on the table, then fine tune an embeddings model on those articles.

From there it would be as simple as demonstrating that we can link organisational assets to information outside of the fictional table, as well as reliably retrieve all the information on the organisational assets from semantic space.

-

Semantic Query Engine

In traditional databases, we have query engines that can interpret stuff like:

SELECT country, capital_city FROM countriesor

MATCH (a:Word)-[:GENDER_RELATION]->(b:Word) RETURN a.term AS feminine_term, b.term AS masculine_termBut to query a Semantic Database would have to be quite a bit more complicated. I can only really speculate here.

Intuitively, I’d think you’d have to have a model parallel to your embeddings model that would somehow learn to explore the semantic space to answer questions. So the query language would be natural-ish. Perhaps you’d say:

"Give me every Asset installed in a location with a high population". You might have a model that extracts the symbols (Asset, Location), qualifiers (high population) and relations (installed in) in the query, which informs an agent to traverse the semantic space, returning hits as they come. The agent might learn to make hops to intermediate symbols. -

Predictive Capabilities

This notion is what led me to this investigation in the first place. For data quality issues relating to incomplete input data - say, incomplete maintenance documentation - we should be able to backfill missing data with predictions from semantic space. We somewhat did this in experiment 1 - we had 20 Country-Capital facts, and learned the Country-Capital relationship from them. We then applied that relationship vector to new Countries and guessed their Capital - mostly correctly. We could do the same with, say, an Asset’s condition. Say the condition score of the Asset was not filled out. If we know the Asset is installed in a rainy location, and the last condition assessment was 5 years ago, navigating semantic space to where the Asset’s current condition would be should yield a guess as to what the null value in the maintenance documentation might’ve had.